Several days after the American Medical Association announced it would suspend its involvement in pediatric gender surgeries and chemical transition for minors, the broader implications of the decision are beginning to come into focus. While early coverage framed the move as another flashpoint in a polarized cultural debate, the action more closely reflects a loss of institutional confidence in a medical model long presented as settled.

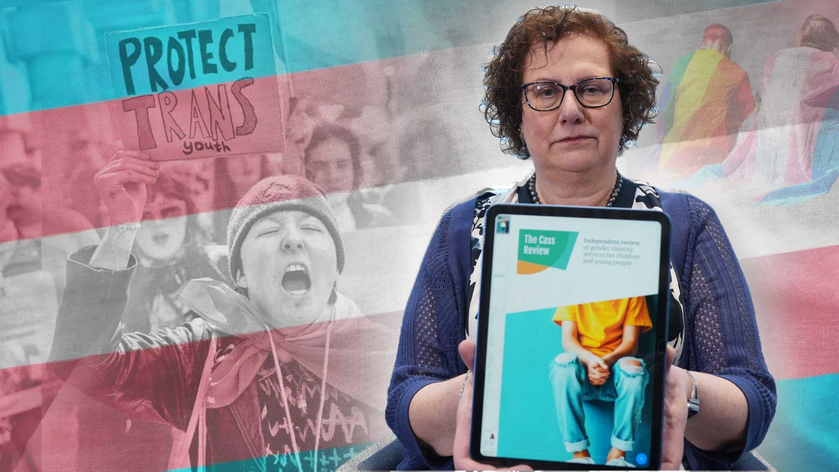

The AMA’s decision follows a growing international reassessment of pediatric gender medicine, most notably outlined in the United Kingdom’s Cass Review, an independent, multi-year evaluation of gender services for children and adolescents commissioned by the National Health Service. The review found that many commonly cited claims about the benefits of medical transition for minors were based on low-quality evidence, including small observational studies, short follow-up periods, and heavy reliance on self-reported outcomes (Cass Review, Final Report, Evidence Base Overview).

The Cass Review did not conclude that all medical intervention was inappropriate. Instead, it emphasized that the evidentiary foundation supporting routine medicalization of gender-distressed minors failed to meet the standards typically applied in pediatric care; particularly when interventions carry irreversible consequences and long-term outcomes remain largely unknown (Cass Review, Clinical Standards and Safeguards).

Within the United States, institutional messaging often conveyed a higher degree of certainty than the evidence warranted. Parents were frequently asked to consent to life-altering medical decisions under conditions of urgency, with clinicians and professional organizations assuring them that benefits were well established and risks minimal. The Cass Review found that alternative explanations for a child’s distress including trauma, autism spectrum conditions, and comorbid mental health disorders were often underexplored prior to medical intervention (Cass Review, Mental Health and Neurodevelopmental Factors).

As those medical decisions became irreversible, a shift occurred in the public discourse. Parents whose children had already undergone medical transition increasingly emerged as some of the most prominent advocates for the model itself, often positioned as uniquely authoritative voices in policy discussions. Their testimony, grounded in lived experience, was frequently treated as dispositive rather than contextual.

The Cass Review helps illuminate why this dynamic took hold. When evidence is limited but decisions are permanent, uncertainty becomes difficult to accommodate. In such conditions, personal medical choices can be reframed as universal necessities; an approach that diffuses responsibility across families, clinicians, and institutions alike. If a treatment pathway is presented as appropriate for all, accountability for adverse or unintended outcomes becomes harder to assign.

Importantly, this pattern does not describe all parents of gender distressed children. Many acted in good faith, relying on guidance from medical authorities they trusted. However, Cass underscores that institutional confidence preceded and shaped parental consent, not the other way around.

The AMA’s suspension does not introduce new scientific findings. Instead, it reflects what the Cass Review documented years earlier: that the medical consensus was far more fragile than public assurances suggested. As major institutions now step back from categorical support, unresolved questions about evidence standards, informed consent, and responsibility are returning to the center of the debate. These things are no longer avoidable, and no longer abstract.

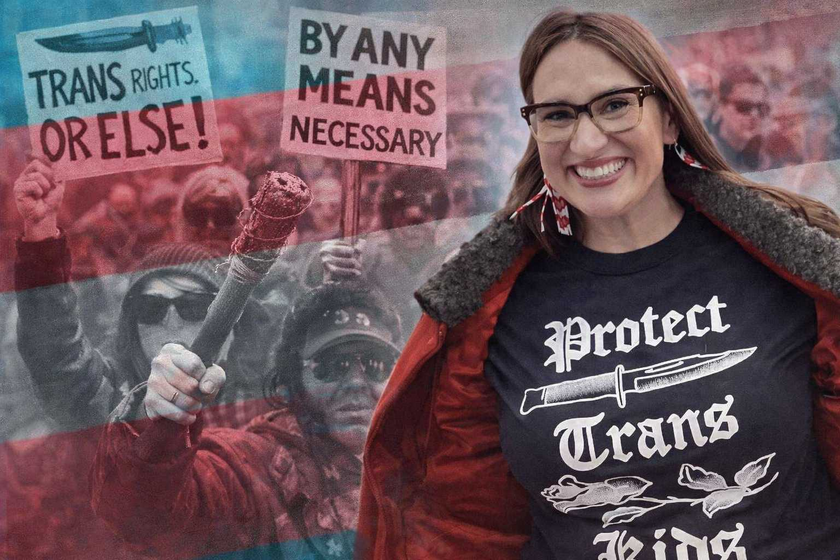

Despite vocal pushback and instances of harassment and violence from some quarters of the transgender community, the medical consensus is increasingly clear: transitioning minors is not the definitive solution. Leading experts now emphasize the importance of comprehensive mental health treatment that addresses underlying conditions and causes contributing to gender dysphoria and body dysmorphia. No amount of intimidation or threats can alter the fundamental principle that care must be guided by evidence, caution, and the best interests of the child.